All You Can Eat by Dimitris Armenakis

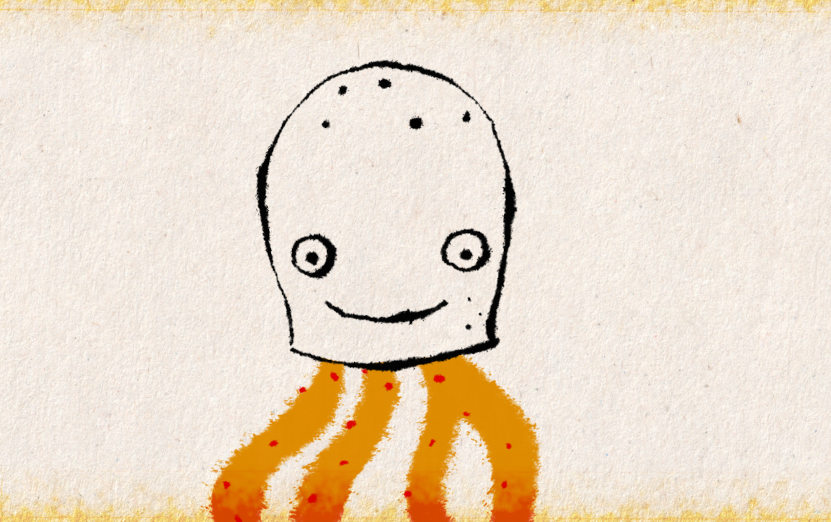

Cartoons are being taken from their habitat and encaged by humans, only to be processed for one reason – to be eaten alive.

The film All You Can Eat by Dimitris Armenakis (recently won the prize for Best Student Film at the ASIFA Hellas 2021 Awards) is a Royal College of Art student film; now premiering online.

Zippy Frames talked with the director:

ZF: Did you actually start the film with the need to talk about consumerism, the idea to defend a more joyful way of living or both?

DA: The idea started with the concept of how our reality is perceived through the means of consumption. What if I told a story through the eyes of the consumed, not the consumer? Gradually, the contradiction between the joyful cartoon world and the dark, dystopian human world began to set the world of the story. As ‘All You Can Eat’ is a short film, I would struggle to compress as much information as possible, yet make the narration understandable to the audience. My first thoughts were to use cartoon characters as products of consumerism in a wider sense, maybe as a method of payment, drugs or anything that humans could actually make use of to a great extent. Then I thought that what sums up all those voracious intentions of overconsumption is the act of eating.

Watch All You Can Eat

ZF:. Did you always have the same story from the start as a kind of adventure story for your characters?

DA: My stories follow the hero’s journey, which is true, but it’s never predefined. The scenario is something I explore constantly during pre-production. Usually I think at the very beginning what the film is about and then whatever happens between the very first frame until the last is something that evolves as I keep working on the storyboard, where I keep adding/removing elements.

Storyboarding and animatic are essential for my working process, as I like to work on sound from the beginning as well, especially where I have very specific sounds in mind for some shots. For All You Can Eat, feedback from tutors and colleagues was vital, as they would spot things that didn’t work within the story, so I’m really grateful for that.; the animatic is just building toward the final film. As I keep finishing shots, the ones from the animatic are replaced, and slowly the film comes to life.

Where character acting is involved, sometimes I even skip key frames and just jump straight into animation. There is a lot of improvisation when needed in order to enhance the character’s emotion. This is a great tool for me, especially when I want to transition between shots; it works nicely. I also leave a few seconds intentionally unscripted on the storyboard, because in my mind I know that I can improvise at that specific point.

ZF: Why do you describe the cartoons as non-binary characters? And which are your influences here? Your cartoons look like the really 'squash and stretch' variety of characters.

DA: In a way the characters are claiming their own narratives, as we’re dealing with a community of creatures whose reproductive system isn’t based on sexual intercourse, nor do they express a certain gender identity. The nature of these beings is what I'd like to explore more in the future. In All You Can Eat, the character's relationship is explored outside of the ‘boy meets girl’ conventional narrative, and the audience can identify as they please, since the characters are neither entirely male or female. This leaves space for their emotional connection to come to the foreground. You can also use it as a comment on the dark ages humanity is going through with lack of sympathy for other living beings inhabiting the same planet as us.

Character design leaves space for facial expressions and freedom to play around with their form and how they interact with their environment. Inevitably, their design is heavily influenced by 1930s cartoon characters, which always impressed me with their elasticity and intense expressions. In a way, it’s an evolving process that initially begun with ‘First Thirst’.

ZF: I was impressed by the rigid, geometrical structure of the city (also reminded me of your Absorbed film). Did you have any actual city in mind or was it a result of various life / cinematic inferences?

DA: Subconsciously, my influences definitely originate from urban structures as well as films whose photography stuck in my mind throughout the years. Absorbed was indeed my first approach to this realm of endless metropolitan dystopia, which matured with All You Can Eat. To be more specific, viewers may identify with buildings from Pireaus, Greece, where ‘Meat Market’ exists, home of the underground Greek music scene, as it rose through the years. Aesthetically, I wanted to depict this juxtaposition of the food market in the morning and music creativity in the night, which I felt was very unique.

During the production I was living in London, a city where I could find even more reference points that could help depict my vision. In 2019, I pictured a human world where people avoid physical interaction, with a polluted grey sky covering the film’s city. It’s funny how the film was already finished before the pandemic even started. Little did I know!

ZF: All You Can Eat being a RCA student film, how did you work in terms of schedule and deadlines?

DA: Planning ahead was my main concern in pre-production, as I always try to ‘buy’ time for the film production in case something goes wrong. In the end, there were always a few frames that needed to be fixed, or some shots would take longer to animate than expected etc. I was working simultaneously on the visual and the audio part of the film from the very beginning, along with Charlie Carroll who recorded most of the sounds heard in the film. Concerning the animation, I tried to make a production timeline as soon as possible, so everyone who helped on the film knew exactly which shots and how many frames they would be colouring/animating. Also, early on in pre-production, I was discussing with Gennadios Arvanitis (Degear0001) about the nature of the cartoon’s voices, for which he used a Casio SK-5 sampling keyboard to record them. Rita Mosss came in to complete the sound design with their track ‘Miss Stranger Bird’, and finally sound mixing was done by João Fonte at National Film and Television School.

ZF: Was it easy to find the right visual balance between your characters and the backgrounds in compositing all together? And how was the process in animation itself?

DA: For some shots, I spent more time drawing details in the background rather than having intense animation all the time. The characters exist interactively with the world, so both elements complement each other. The simplicity of the characters and their vivid colour palette made them stand out from black and white, industrial backgrounds. Sometimes I would use 3D models in order to work on the perspective of buildings or the lighting; you can see in the last shot where the characters hide in the trash can. I created the 3D animation, and afterwards the exported image sequence was traced through hand-drawn animation. This technique meant that I’d sometimes have to animate the same movement twice, once in 3D and then again in 2D, but I managed to get the right look for the world in order for it to fit with its characters.

ZF: Some people would interpret the film as a fight for independent art to find its own way in the garbage bin of mass consumerism. Would that interpretation appeal to you?

DA: In the 21st century where a rapid overflow of information reigns, ‘All You Can Eat’ is inevitably a political statement, a moment to question where we stand at this point. Art is about unbiased, truthful emotions that come from within, hoping to change someone else’s life for the better. Within the realm of digital media, independent art will always find its way to the surface, especially as the medium of animation is evolving and more people are engaging with it. Animators are storytellers who use a certain medium each time to convey a message, which will always find its audience.

Film Review (Vassilis Kroustallis):

Armenakis builds his noir thriller story as an adventure in disparity, always present between his characters and their new environment. The film starts as a modern-day utopia of self-sustainability, before it reveals an urban cartoon nightmare. It is easy to empathize with Armenakis' Fleischer-like characters; they are simple, expressive in their movements and daring in their actions. It is also effortless to feel the angst and uneasiness that the big grey city causes. Rigid lines and big, high structures dominate the field. The interaction between these two (characters and their environment) provides its own sense of urgency in a world where cartoons are the instruments of mass consumption. With an assured pace that flows from one scene to the next, and a sound design that increases the character's helplessness, All You Can Eat is a well-placed parable on cartoon and animation art, which needs to find its place in the garbage bin in order to survive. Hopefully, its representative can come out again in the open.

About Dimitris Armenakis:

He is an animation director. He graduated with a BA in Audiovisual Arts from Ionian University in Corfu, Greece and in 2019 he graduated with an MA in Narrative Animation from the Royal College of Art. He is working as a freelance animation director.