50 Years of Making and Teaching Animation in Brazil: Núcleo de Cinema de Animação de Campinas

In addition to, and also because of, the celebrations of Monstra Festival's 25th anniversary, the festival also paid tribute to the 50th anniversary of the 'Núcleo de Cinema de Animação de Campinas' ('Campinas Animation Cinema Center'), a center for animation production and education coordinated by Wilson Lazaretti and Maurício Squarisi, two bastions of Brazilian animation.

Wilson Lazaretti, Maurício Squarisi, and I met about 20 years ago at festivals around Brazil. It is always a pleasure to meet them, which happened this year at Monstra, in Lisbon.

Lazaretti's invitation to teach “little cinema” (super 8mm) classes to children at the Carlos Gomes Conservatory in Campinas marked the beginning of the Núcleo's activities in 1975. In 1980, other artists, including plastic artists, ceramists, poets, and other professionals interested in animated cinema, comprised the group, with the name Núcleo de Cinema de Animação de Campinas. However, a year before, the then-visual artist Maurício Squarisi joined them. Over time, Lazaretti and Squarisi became the group's core, focusing on teaching methods for animation through workshops.

They've conducted over 2,800 workshops in Brazil and other countries, including the US, Portugal, Denmark, Mozambique, Argentina, and Croatia. As a result, they have a solid animation production, with more than 350 short films from these workshops, becoming a national and even international reference.

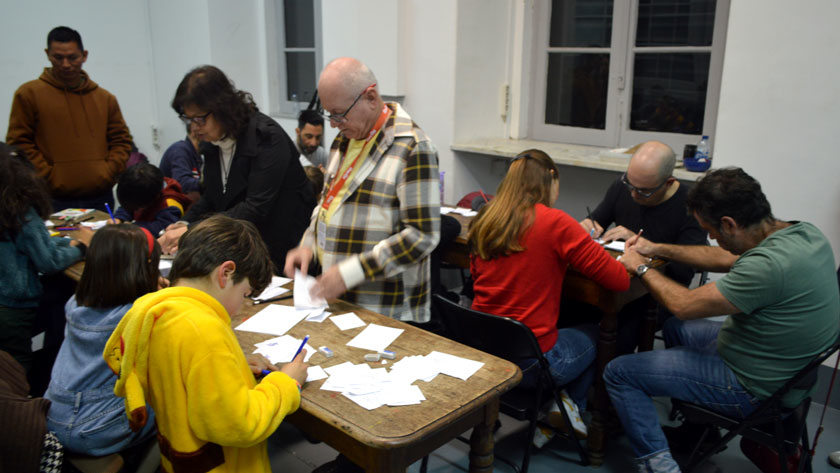

Núcleo de Cinema de Animação de Campinas Monstra 2025 Workshop

In 2015, they released their first feature films: 'Café, Um Dedo de Prosa'/'Chatting About Coffee' (Maurício Squarisi), which "tells the drink's (coffee) story and its influence on Brazilian history,” and 'História Antes de uma História'/'Story Before a Story" (Wilson Lazaretti), which “tells the story of Dr. K, an old man who, during one of his walks, finds several objects along the way that will help him unravel the great mysteries of animation techniques”.

Café, Um Dedo de Prosa

This year, they presented a talk at Monstra entitled 'Half a Century of Animation with Kids, Youngsters, and Indigenous Communities,' which provided an overview of their 50 years of work. The talk highlighted the workshops held in the indigenous villages of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, located in the Amazon forest. They also taught animation workshops with zoetropes to 'parents and children'.

I spoke with the duo and am bringing our lively conversation about the highlights of these 50 years of workshops and the unique experiences my friends have had while providing them to residents in remote areas of Brazil. I noticed the conversation was very dynamic, and the answers went far beyond the questions.

ZF: Please highlight important moments in this 50-year journey of organizing and teaching workshops for us.

WL: A special moment, right at the beginning of the Center, was our visit to the 'National Film Board of Canada' in 1980. It was our first international animation trip, and we went to show what we were doing at the time. Embrafilmes supported us, enabling us to take some 16mm films. You know us; we've always been like that. We took an independent path in animation, never learning how to make cartoons like others do for commercial animation production. Therefore, I was interested in observing the work done by the professionals in the field.

Then, I had the opportunity to meet Norman McLaren. What did I learn from him? I am not sure. When you meet your idol, you keep quiet, right? He was very approachable, and we spoke in French. He believed that what happens between one frame and the next is the most important aspect of animation. But for me, the most important thing is what even José Manuel-Xavier (who turned 80 and had a talk and an exhibition during the festival) emphasizes: the essence of animation is to put one drawing after another (laughs).

Another decisive moment was in Zagreb, where I was with animators from Italy and David Ehrlich from the United States. I think we met in the garden, and we founded what is now the 'AWG Asifa Workshop Group'. At that time, the organization was 'Commission Number 5'. I also had contacts in Yugoslavia, now Croatia. So, you build your way, right?

ZF: And the work of the Center with the Indigenous Peoples, how and when did it begin?

WL: We have been working with the Indigenous Peoples since 1991. That was also a defining moment.

MS: The most memorable moment for me was the first time we went there... One morning I was on the edge of the Rio Negro beach, and some Indigenous children appeared, all wearing Salesian uniforms from the Salesian school.

WL: They have been there for 350 years. They do some positive things. The indigenous people themselves affirm this. Anyway, it is still wholly colonialism, shaping the way of thinking.

MS: I felt sorry when I noticed that scene of colonized, deculturated indigenous people. That is when they came onto the beach playing, throwing water at each other, and everything like that. Then they left, like that, drying off, like that. Then I realized that this uniform does not mean anything. Inside, there is an indigenous soul, a Tucano, a Baré.

Another moment was also in the Pantanal. Years before, you could only reach Corumbá, about 150 kilometers inland in the Pantanal (central-west region of Brazil), with a 4x4. An isolated region, but there were boys with amazing drawings, and why were those drawings so impressive? They had no visual references. There were no comics, no television, nothing. When they drew an armadillo, it was its first graphic representation. That was when I understood what Picasso was saying: that he spent 90 years learning to draw like a child. That was when I saw what he meant.

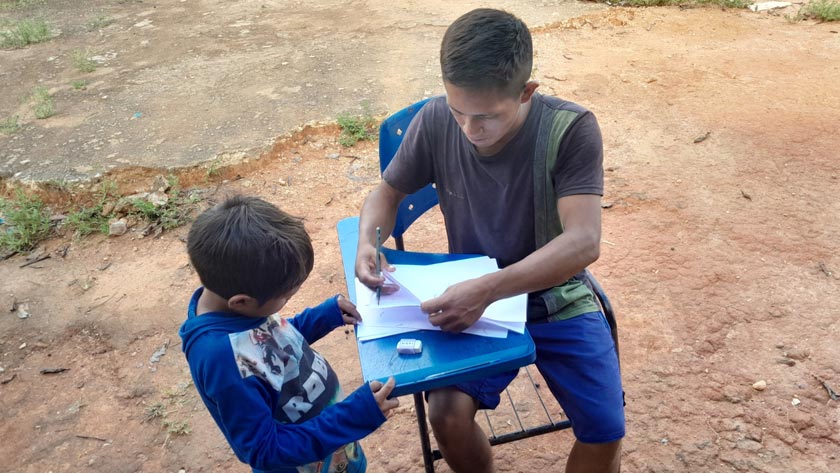

Núcleo de Cinema de Animação de Campinas animation workshop

WL: Backing to the city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, a municipality of the Amazonas state (Brazil). In 1991, it was our first time there, and we created a link with the city. And now, 34 years later, Hermes Soares Miranda, an indigenous student of the Piratapuya ethnic group, has appeared in the 'Unicamp' (State University of Campinas) program in São Paulo, dedicated to indigenous students. My subject at Unicamp is free; it is an elective discipline in this program. He was at the back of the auditorium for the first five days. Then, I said, "Now, each one will do it."

I explained the philosophy behind our animation approach. However, he thought he would learn how to animate at the university in a Disney-style animation. I explained, "No, here everyone does their own work," and I guided them. I said, “The drawing is already inside you. The animation is there too. We're just going to let it emerge naturally." I teach with a light-hearted, imaginative approach, unlike Disney's style.

Of course, there is also the issue of whether you value the trace. Although there is always a boy or a girl who draws in a manga style, this negative behavior is not natural for a kid who is just starting to create. I believe they have to learn to draw things from within themselves and not start copying commercial styles. They need to develop their unique style of expression. That's what I think.

ZP: This is the unique aspect of working with indigenous people.

WL: That's right. All indigenous people draw. They see drawing as a way of expressing their culture. For example, they are at Unicamp to portray indigenous legends.

ZP: And how many indigenous people does the Unicamp program receive?

WL: The university has approximately three hundred students, representing about forty diverse ethnic groups. But they are all in the same place, which generates disagreements because the 'Piratapuya' don't like the 'Tucanos'. I had students who asked not to work with each other. I replied, “Look, I have nothing to do with this. It’s a longstanding issue; I trust you all can resolve it. We will need to handle it here and work together, okay?”

In the upper Rio Negro (border with Colombia) there is the FOIRN. FOIRN is the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of the Rio Negro, in Amazonas. In this region, there are approximately 23 different ethnic groups. FOIRN can help us with the structure to go to São Gabriel to teach the course, and there is a small structure there: lodging, a boat, and fuel.

ZF: But what are the workshops like in the villages?

WL: The last one we did was in the 'Yanonami' community, 'Maturacá', in May 2024. It’s 2,607 km from Campinas to Manaus and 851 km from Manaus to São Gabriel da Cachoeira, so we traveled 85 km on a dirt road to get to the Yá Mirim bridge, from where we continued on a 6-hour boat trip across four rivers.

We set up the zoetrope for the Cacique (the village chief) to see how it works. He started looking at it. He looked. And he said, “Yes, you can stay.” If he disagreed, we would have to go back because the land is theirs, and we must have authorization to stay. So, we first worked with the zoetrope, and then they started doing something a little more extensive, using sheets of paper and a light table. But they drew on their legs, like on their thighs, you know? And it’s not a very accurate drawing... but they decided what they wanted to do.

The short film is a representation of a Yanonami dance, 'Prai-Prai' ('Come dance'). They made it, and we filmed it with our cell phones. We also filmed it in Campinas and scanned it. I have it with me; we’ve already sent it to them. However, they didn’t authorize us to show it.

Watch: A short strip of "Prai-Prai Making of, Backstage" (2024)

ZF: What do you think is crucial in teaching animation to children?

WL: I believe no one should teach children to draw animals to work in the industry; I don’t think it’s fair. I think it has to be a more creative and open process. And do you know why? Because when I tell the kids, “Look, I’m going to take the film to Portugal, right? The kids there will want to know: What are the kids in Brazil doing? Oh, that’s what they’re doing. But what are they feeling? Oh, it's solidarity or something similar."

I forbid it; no weapons, punches, or kicks in the film or cartoons. No violence. And the students ask, “Oh, but why, teacher?” I answer, “You often see it on the internet. Create something different.” I tell the kids, "You’re not violent, so there’s no reason to portray violence, selfishness, or anything like that."

When we started, the United States was producing commercial films to attract children, whereas the Soviet Union (despite its repression) was creating films with a different approach. I don't know if it was better or worse, but it worked better with the children.

ZF: Yeah, I got what you mean. However, what is the Núcleo currently working on? Is it another feature film?

MS: Yes, the title is 'Vapor Speranza' ('Vapor Hope'). The story revolves around Italian immigration (to Brazil), drawing inspiration from my own experiences.

ZF: A beautiful, romantic title, it resonated with me. You're of Italian descent, right?

WL: Yes. My grandfather used to tell me these stories, and I researched them extensively. Vapor Speranza is the name of the boat he came on in the film. But in fact, it was called San Gottardo. The film is a mix of documentary and fiction. I'll start by changing the name of the boat (laughs).

ZF: Thank you so much for all this testimony, Lazaretti and Squarisi. Moreover, congratulations and thank you for these 50 years!

WL: Oh, as for the workshops, when you teach something, you learn much more than you teach. So that's what has happened to us until today.

I couldn't have ended this story any better. I hope our readers enjoyed it too.

Wilson Lazaretti, Maurício Squarisi and Eliane Gordeeff at the 2025 MONSTRA Festival

Núcleo de Cinema de Animação de Campinas Brazil workshop photos by Núcleo de Cinema de Animação de Campinas. MONSTRA workshop and interview photos by Claudio Roberto

Contributed by: Eliane Gordeeff