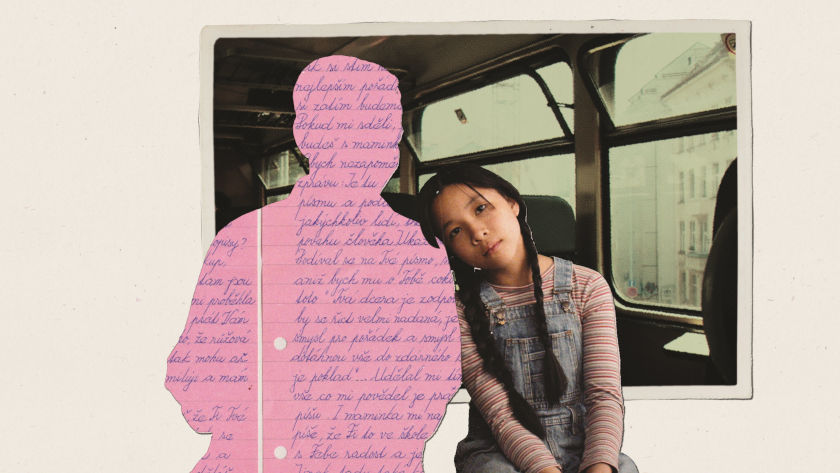

“For Me as a Director, It Felt Like Sculpting”: Interview with Tomás Pichardo Espaillat on ‘Olivia & the Clouds’

A partly abstract fable of love through time and space: Dominican animator Tomás Pichardo Espaillat’s ‘Olivia & the Clouds,’ which premiered earlier this year at Locarno Film Festival, comes next to Ottawa International Animation Festival (OIAF). Written and directed by Pichardo Espaillat, the film is the Dominican Republic’s first indie animation film for adults unique for the filmmaker’s usage of countless animation techniques that together visually depict the fickle — and sometimes formless — nature of memories. Through different timelines, the film reveals its secrets through the stories of several people haunted by or confronting strong emotions and recollections of love that manifest, through magical realism, in different ways. ’Olivia & the Clouds’ is inspired heavily by the filmmaker's own “ghosts, stories, and conversations,” as credited in the end titles.

Zippy Frames spoke to Tomás Pichardo Espaillat about his film’s unique combination of styles, the sonic landscape, and some of the film’s key elements of magical realism as explored through commonplace things.

Zippy Frames: This film is bursting at the seams with so many animation techniques — it’s certainly one of the most stylistically inventive animated films I’ve ever seen. How did you begin piecing them together?

Tomás Pichardo Espaillat: I didn't have formal animation training. I never went to animation school. I come from a fine arts background, and the way I learned animation was through commission work. Especially, I was working for TED-Ed, and I did 24 short films for them. In each project, I wanted to learn a new technique or a new style, or experiment and play around with it based on their story and based on the ideas of that specific script. At the same time, I had the script for Olivia and the Clouds written and I just felt like, oh, maybe I can try this on these elements and these different techniques on the film.

Here in the Dominican Republic we don't have a full animation culture or a full industry of animation, so all the animators that work here come from different backgrounds. Making a film that was cohesive throughout was sort of out of the question with the kind of people that we could find. So I was thinking, what if we build a feature film that is full of techniques because the story allows for it? The story has different points of view, and the way the characters think of memory or think of other characters changes and how they behave in one story and in the other story. We were thinking, what do we play with that, also with the visual style, with the animations? In terms of different techniques, we were just trying to find what worked for each character, what worked for each moment. It was very intuitive. It was not analytical in the sense that we were playing around. For me as a director, it felt like sculpting: people were animators, were making stuff and building stuff, and I was just putting in specific moments and seeing how it felt for that specific scene.

ZF: Could you elaborate on some of the strengths that the animators brought to the film?

TPE: Most of them used to be students of mine. I was studying abroad in different places, and when I came back to the country, there was not a specific animation school, but there was a film school. I started teaching animation within the film school. My approach to teaching was not teaching a specific program, software, or a specific technique. It was just about building stories in animation and playing around with animation. As they were working on their projects, I was identifying things that they could do and what they were passionate about. Some of them were passionate about stop-motion and cut-out techniques. It was a very fluid method for me to bring them to the film. I understand how they work, their strengths and their weaknesses. Some of them were working directly through the animatic.

For specifically the abstract sequences, I was just treating them like actors, like performers in the film. I was telling them, “This is the feeling that I want to portray in this scene.” You don't have an animatic, it's just a few moments that you can play around with the techniques that I know they have. For example, in the bachata sequence at the bar. I had four or five different animators doing different moments from that, and I didn't want any of them to see what the other was working on. I just told them what I wanted in the scene, what I wanted for the character of Olivia to feel at that moment. They just were playing around with different techniques, with different styles.

ZF: Can you talk about the film’s music? I love that the credits include a clip of the composer playing an instrument — we get a peek behind the curtain of the process.

TPE: He’s from Turkey and his name is Cem Mısırlıoğlu, and he's an old collaborator of mine. We have been working together for 14 years now, and we met at Parsons School of Design at The New School in New York. I was in the illustration department, and there was a class that was mixing illustrators with jazz musicians. So in that class, they paired one illustrator or one videographer with one musician, and by chance, they put us together. We clicked very well, and we started working and collaborating after that. And for us, it felt like a conversation. For example, I do something and he reacts to it in music, and with that, I react to that. All our projects felt like that. For this project in particular, I wanted him to be involved in the project because we've been collaborating for a long time, but I also wanted the project to feel very Dominican in the sense of audio or a sonic experience. So he came to the country and did two weeks’ research of everything. We went to the countryside just for him to listen to the river to see how it sounds. We went to the very chaotic parts of the city, just for him to listen to that. We would talk with different people about different instruments, from our African background, our Native background, our European background, because the Dominican Republic has these multiple elements and for him to absorb that and not just to replicate that, but to give something to it.

ZF: The sound as a whole is quite unique and vibrant.

TPE: For not only the music but for all the sound, I wanted to make it feel the way Dominican Republic and Santo Domingo sound in particular, because something happens in live action films here. Because of the film education that they have, they try to recreate the things that they are inspired by, and they study other movements from other countries. When they start making films, they get inspired by that. It's really good that those inspirations are very helpful with that, but they sound very silent in comparison to how Santo Domingo really sounds. I wanted to bring all that sound to the movie because that's how I feel. I open the door, and all that sound invades me. So that was very important for me when we were talking with the sound designers, I was telling them that I need all these textures of sound because it's very important.

With the voices, with actors in general in the Dominican Republic, the accent is sometimes very difficult for other countries to understand us, and we have to water down our Spanish and speak really slowly and put every word where it's supposed to be. You see it in films, and you see it in television — it sounds awkward. For the casting process, I didn't want that. The way I did it was that I asked everyone to send a voice note talking and about someone they know. It could be a memory from someone. I just want to hear the way they sound in real life, and how they express about other people and memories and how they feel. That’s the way I built the team of the voice actors by the way they sounded, and the way they talk about the people they know, the people they love, or the people they hate. That made me understand, oh, this person might be right for this part.

ZF: There’s a sequence in the film where you overlay animated characters over live-action outdoor shots on film at a bustling market. Almost the entire rest of the film is animated, except for the credits. What brought you to this technique for this sequence in particular?

TPE: Before I started making animation, and let's say, around 13 or 14, I wanted to make films, but I wanted to make them in live-action. I didn't understand what animation was. I didn't have money to buy a camera. I was very shy to get in contact with people to act in my film. So I was doing animation as a replacement for live action for maybe later on. Through that process, I became an animator. Throughout the years, I realized, no, I don't do that — I do animation. But there was a period where I was combining both. I was mixing elements on film in maybe 16mm or Super-8, and the sequences that were very expensive to film or maybe had like a camera movement or several actors I was animating instead. In that process, I really enjoyed those years and when I was doing this film, it has a lot of elements from all over the place in my head. So I wanted to add a sequence that matched that moment in my life of live action mixed with animation. And a little bit about the market that is in the market sequence shot in Super-8 no longer exists here in Santo Domingo — I like that it’s a documentation in the sense of something that no longer exists that is captured on film.

ZF: Was this older footage you drew from?

TPE: We shot that in 2022. The new government was changing that area, because it's a chaotic market, and they wanted to to make it a more pleasant market. So they changed all that completely.

ZF: You use a lot of nature-based living metaphors in this film, including clouds and plants. For instance, there is the appearance of Jupiter, which takes on a life of its own.

TPE: I lived in Argentina for a while, and they were using a big telescope to see Jupiter. It was the first time I saw it really big. It felt like it was moving. All of the shapes stayed in my mind. Then the other part of what the Jupiter place is, where they go in the film — that came from a dream that I had. In the dream, I was in this river that was made out of watercolor painting. Sometimes I dream in animation. In the river, there were fish made out of paper. What I did in the dream that is not in the movie is that I took all the fish and I opened them, and what was written on them were stories and elements from my past. That happened a long time ago, but when I saw Jupiter in the telescope, I connected to that dream. I remembered a dream. I was like, these two places make sense. I had it in mind while I was writing, and I needed a sequence in the movie where Ramón brings something from the world to show to her. There was the phenomenon that I saw 10 or 12 years ago in Argentina — it happened again that Jupiter was very close to the Earth. So we photographed Jupiter in real life and used it in the film.

Watch the 'Olivia and the Clouds' trailer:

'Olivia & the Clouds' screens at OIAF, 25-29 September 2024