“We Learn Too Slowly About the Environment”: Michael Dudok de Wit on Animation and Ecological Awareness at Anima Brussels 2025

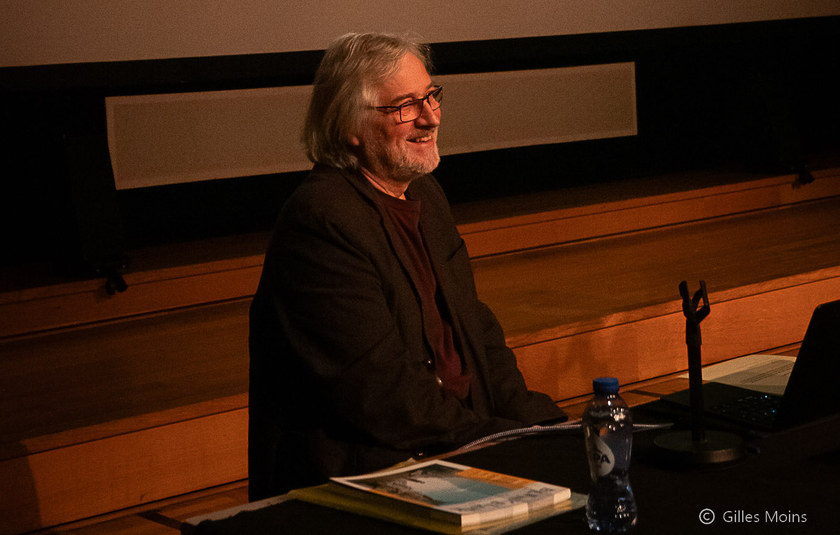

“It’s a bit of a contradiction to put animation and ecology in the same sentence because animators are usually indoors—we try to avoid direct sunlight when we work because it interferes with our screens.” Oscar-winning Dutch animator Michael Dudok de Wit ('Father and Daughter', 'The Red Turtle') began our interview at Anima Brussels (Brussels International Animation Film Festival, 28 February–9 March 2025) with a half-joke, half-truth about the connection between animation and everything related to the environment. Green animation, climate-friendly production, environmental filmmaking: these buzzwords all signal a growing area of interest for the film sector writ large, but the meaning of such is perhaps all a bit fuzzy. At Anima Festival, Zippy Frames sat down with the London-based animator to dive into these topics and his perspective on what “ecological animation” means for him.

During the festival, Dudok de Wit was further tasked with presenting a talk titled Animation and Ecological Awareness, the connective tissue he admits he once didn’t think about so directly. Now, he suggests that “we learn too slowly about the environment—which he doesn’t see as a good thing. His dialogue-free, Studio Ghibli-produced 2016 feature 'The Red Turtle' tells the story of a man shipwrecked on a nature-filled island, where he repeatedly encounters the titular animal who blocks his escape from his isolation; the film premiered in the Un Certain Regard strand of Cannes and later secured the London-based animator his third Oscar nomination.

However, upon its acclaimed world premiere, he was initially stumped by how it was received: “A spectator came to me and said some very nice things about the film, and then said, ‘I like the ecological message of your film.’ I remember looking at him as if I’d never said the world ecology during the whole production phase. Then, I thought about it: deep respect for nature is the root of ecology.” This was one of the key points that Dudok de Wit remembers recounting in his letter of intention for 'The Red Turtle'; his “profound respect for nature”. But “to be able to somehow communicate that feeling through film, in my own way, and without preaching, especially without being didactic, was a challenge,” he said.

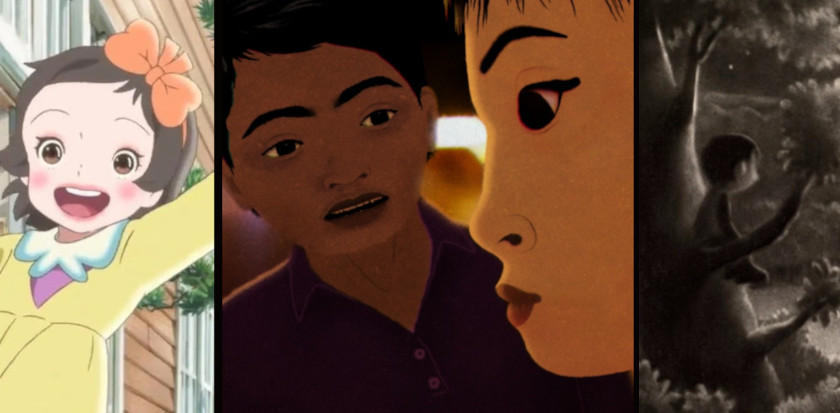

A still from 'The Red Turtle'

During his presentation for a packed audience, he broke down what he saw as three elements to consider when examining the intersection of animation and ecological awareness. These were ecological production, ecological content and narratives, and a third, more subtle element, which he described as appealing to “animation as an interplay between art and entertainment.” The first two are the more straightforward, easier-to-understand aspects of an ecological approach to animation. As he explained, non-profits like Paris-based Ecoprod are championing “eco-responsible” animation. The downside is that an eco-friendly approach to the production process is often quite expensive, as it now stands, which is a deterrent to green filmmaking. However, more and more countries across Europe are seeking to develop new standards and incentives for making animation more environmentally focused.

On the content side, there emerge several methods to develop ecological messaging. Dudok de Wit described his approach as intentionally much more peripheral, all while acknowledging the impact of films such as environmental documentaries and those that urge viewers to take immediate action. He also pointed to the 1987 Oscar-winning short 'The Man Who Planted Trees' by Frédéric Back as an example of a very effective environmental narrative, or the historical fiction novel 'World Without End' by Welsh author Ken Follett. He says he prefers to shy away from didacticism and imperatives, leaving the audience to draw their own conclusions. Rather, he “work[s] with symbols and metaphors to touch people on a more subtle level.”

In his talk, he furthered this idea by referencing the idea of the collective unconscious as popularized by Carl Jung, a theory that certain archetypes and symbols are shared by all humans, regardless of background; these include concepts like light and darkness as opposites. Dudok de Wit says he builds upon this by allowing the unconscious to reveal itself through his films, driven by these shared ideas that don’t need to be actively pointed out. “We are highly dependent on our subtle perception and sensitivity,” he clarified.

This follows along the same lines as why there is no dialogue in 'The Red Turtle', and furthermore, a refusal to anthropomorphize animals in much of his work: “I find that the language of animals touches so deeply. Maybe it’s due to some very ancient memory that I prefer to go in that direction.” He expressed a strong appreciation for Gints Zilbalodis' approach to 'Flow', which shares the dialogue-free trait with 'The Red Turtle'—even if there are tinges of anthropomorphism in the film, as he says, but these aspects also evoke astounding emotion. “What's also so beautiful about animals is that they don’t speak like humans,” he added.

For the third aspect of animation and ecological awareness, he turned to examining how being in tune with our environment allows for more nuanced filmmaking: namely, how animating with the intention of being both artistic and entertaining creates an effective product. Pointing to examples of playing with light and shadow, including in 'The Red Turtle', he explained how selecting shadows in certain aspects of animation tells us a plethora of important information. This includes aspects of weather, time, and symbolic details that linger with the viewer without them even knowing. Likewise, using qualities and colors of light evoke aspects of mood, capturing environments in a more compelling—and entertaining way—while also staying true to representing our natural world as authentically as possible.

A still from 'The Red Turtle'

Closing out our conversation, Dudok de Wit shared a bit about how nature and the environment do play a major role in his life; he creates a drawing every day, often for a friend, which frequently returns to themes of nature: “water, trees, vegetation, and sometimes animals.” Even if there seems to exist an innate conflict between the overly controlled environments of animated worlds and the chaos and randomness of the Earth around us, the Dutch animator declares that it’s a false binary: “What’s typical about animators is that we are very much craftspeople. We like the smell and the sound of paper. We like touching different bits and pieces that are not necessarily nature, but it’s close to nature in that sensitivity. It’s the appreciation of ordinary textures and ordinary beauty of color and color combinations.”

Put that way, there is something very simple and beautiful about the connection between animation and nature. Perhaps as we more deeply respect the art of animation, we’ll learn how to more deeply respect the Earth, too.

Anima, the Brussels International Animation Film Festival (also known as Anima Brussels), ran from 28 February to 9 March 2025 in Flagey, Brussels.